The hackathon Coding Dürer took place exactly three weeks ago. Now it is time to take a look back. What are lessons learned? What is the way ahead?

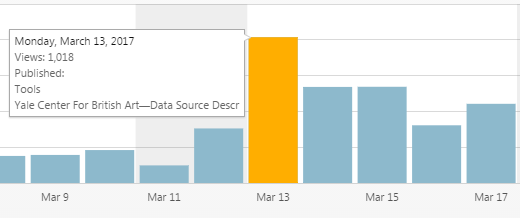

In addition to the lively working atmosphere of the international participants, the active involvement of many people via social media and live streams had been extraordinarily successful. On Monday alone we had over 1,000 views on our website. Since its launch in November the analytics rose to over 14,000 views.

Two blogs reported on us. And the hashtag #Coding Dürer worked fantastically to spread what we did over the five days and to get responses from people, who could not be there with us. Alex Kruse has analyzed the hashtags wonderfully and published his R-code on GitHub for everyone to use.

Post #CodingDurer Twitter Analysis. Code on my GitHub. Thnx again to @HxxxKxxx for organizing. pic.twitter.com/JbVjCxBv0S

— Alex Kruse (@krusealex2013) 21. März 2017

Alison Langmead from the department of History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh gathered colleagues and students in front of a big screen to watch the live streams and twitter as if they were in Munich. That was the kind of involvement I dreamed of.

Ready, #CodingDurer! pic.twitter.com/9lpw0YVQOl

— Alison Langmead (@adlangmead) 17. März 2017

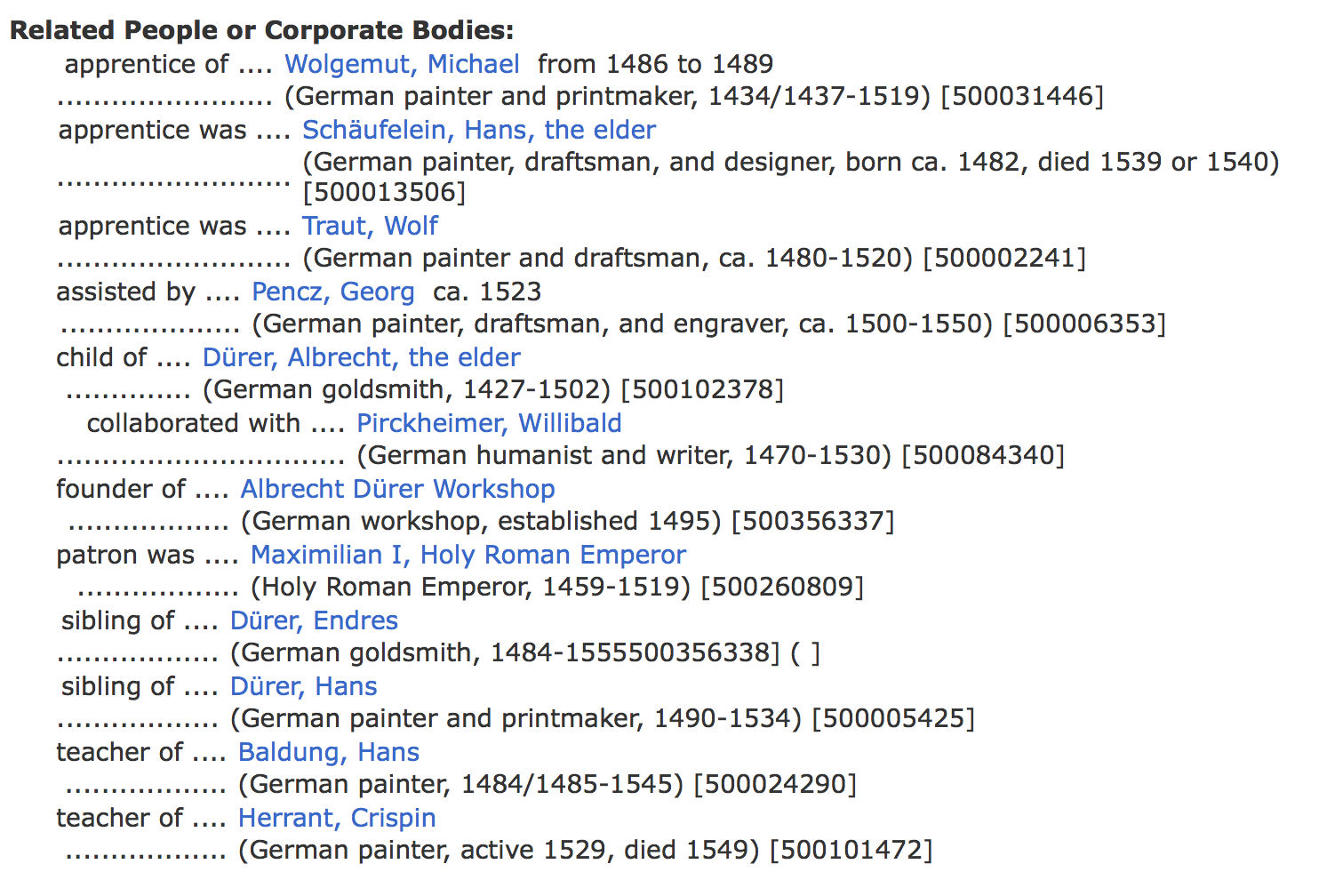

The final presentation has shown beautifully what we accomplished in only a few days. Until today, the live video has been watched by almost 250 viewers from all over the world—not bad for such a specialized topic. We have seen the results of seven teams: The Rogues, Similarities, Metadata, Chatbot, VABit, Dutch Church Interior Paintings and Tracing Picasso. I have put together a few information about every project on the press page—additionally some teams have documented their work in dedicated project websites or in blog posts, others are still working on that. This is a great help to follow the development of the projects, their challenges and results, and thus giving others the chance to get in contact with them and continue the work.

Now is a good time to reminisce what the conditions have been for such a productive and creative outcome. Along the way, everyone has learned so much. What I have learned is that the selection and formation of the groups is crucial for interdisciplinary collaboration. Having talked to many, it seems to me that the following points are important:

- The size of the group. An interdisciplinary group of art-historians and information scientist is in need of many skills. Therefore it should not be too small. On the other hand, the bigger it is the more communication overhead is necessary. A team on 6-7 participants seems to be ideal.

- The balance of skills. The technical realization starting with data cleaning already needs a lot of man power. But having too few art-historians, the group would lack the continuous contextualization of the work in regard to the research question. Balancing the group is, thus, key. In addition: To have a few people experienced in both fields or a designer who can bridge both spheres would be ideal.

- An internal project management. While we have had frequent plenum discussions to have every project know about every other, this is also necessary within the group in order to keep everyone up-to-date about the current challenges and goals and assign a role to every participant. Also: The use of visualizations such as flip-charts or simply papers taped to the wall help very much the interdisciplinary communication.

The Post-It wall seems to have served that need quite well, maybe in an unexpected way, but could be streamlined next time in order to achieve the goals above even better.

What were lessons learned? According to the participants, who filled out a feedback form, everyone was excited about the course of the week, the thrilling discussions on art from different viewpoints and the astonishing results. One project group proposed that it would be better next time to contact data providers beforehand—as they downed the Getty servers several times! For this reason, it would be productive to have technical support at hand, such as server space. People from different backgrounds had different needs and expectations, but they agreed in one thing: More time to work until late at night—and more coffee and snacks throughout the days!

To me, Coding Dürer has given a glimpse of what Digital Art History could be in the future. It has shown that the technology is there, we just need to bring the right people together. I have the feeling we have prepared the soil for many projects to keep growing. And I have the strong believe that it has not been the last Coding Dürer. With the things we have learned, we have to plan for a Coding Dürer 2018 already. I welcome every funding organization or sponsor to get in contact with me to pave the way into the future of Digital Art History.

Thank you @lalisca for everything!

What are your thoughts?